A systems-psychodynamic approach to supporting the psychological wellbeing of staff and students in higher education.

By Charlotte Williams – Organisational Consultant, Tavistock Consulting

Historically in the Higher Education Sector, the approach to staff and student wellbeing tended to focus on helping those whose mental health had deteriorated. In recent years there was an increase in awareness of, and a decline in the mental health of, the student population and as such, the demand for university counselling rose to an unmanageable degree. As a result, there has been increasing focus on the promotion of individual resilience through the promotion of psychoeducation and self-help resources. Similarly, many universities have historically provided staff counselling for their employees facing mental health difficulties, with a more recent focus on wellbeing catered for through the provision of resilience courses, mindfulness and classes aimed at physical health, for example yoga. In either case, the individual, to varying degrees, has been considered largely responsible for maintaining their own wellbeing with an implication that their ability to cope with the increasing pressures of working or studying at university is being put down to their own individual resilience levels. Whilst individual levels of resilience play a part in one’s ability to manage stress and the demands of university life, such an approach absolves organisations of responsibility for how it might operate and impact upon the psychological wellbeing of its staff and students.

Thanks to Student Minds, Universities UK and other key organisations, there has been increasing recognition of something more comprehensive and the need for a whole institutional approach to tackle and support the mental health and wellbeing of students and staff within Higher Education. As a result of this, we are beginning to see how considerations around wellbeing can be worked into the structure of courses and assessment, and the student transition into and out of university. As yet, however, we are not seeing an improvement in staff and student wellbeing.

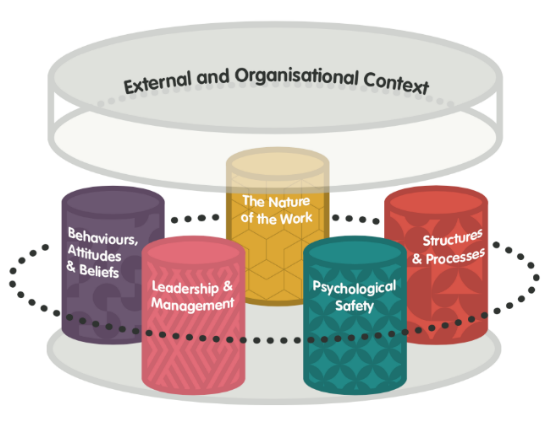

The Tavistock takes a psychodynamic-systems approach to wellbeing and upholds that both the nature of the task, the context within which with the institution finds itself and the structures and systems of the organisation itself impacts significantly upon the wellbeing of its staff. In a piece of work undertaken by the National Workforce Skills Development Unit last year, the Tavistock developed a new five pillar approach to creating and maintaining the supportive organisation within the NHS and I believe that this is equally relevant to Higher Education.

This new approach acknowledges that people in organisations are different, both in terms of their current circumstances and their life experiences, and therefore accepts that there will be varying levels of psychological resilience at any given time. Whilst providing information and services to assist the individual to regain, maintain or increase individual resilience it also recognises that the organisation itself plays a key role in the psychological wellbeing of staff and proposes a framework to consider how to create and maintain what we call a ‘supportive organisation’ within which people with different levels of resilience can not only survive but thrive.

The model proposes five main pillars within an organisation that impact upon the wellbeing of its members. Each of these pillars is interconnected and all exist under the influence of the current economic, social and political climate. If all these pillars are regularly engaged with, discussed, and taken seriously, organisations can use them to find ways of providing the best possible environment within which staff and students can thrive and contribute to achieving the organisational aims.

Image by the National Workforce Skills Development Unit

Of course, no organisation exists in a vacuum and this is especially true in Higher Education where the external context exerts multiple pressures that cannot always be controlled or predicted. The stronger the pillars within your organisation, the better equipped the people who make up your organisation can manage and respond to those external pressures whilst attending to the task in hand. Let’s take a look at the five pillars and how they relate to the HE context.

Leadership and Management

There is a growing body of literature highlighting the importance of effective leadership in organisations. We know that leadership is important for optimising workforce efficiency. It is also an important mechanism for creating organisational culture.

Wilfred Bion, a twentieth century psychoanalyst developed the concept known as containment (1957, 1959, and 1962). It was originally related to the process between a mother and infant where the baby, unable to tolerate its overwhelming primitive emotions communicates to mother through crying. In response the mother takes in this raw emotion, processes it by thinking what this could be about and what the baby might need and responds accordingly – often this includes the mother checking out calmly and without too much urgency or panic whether or not she has understood the distress being communicated ‘Is baby hungry? Or ‘is it the noisy car in the street that’s frightening you?’. Of course baby can’t talk so she may need to take the child to the breast to see if that alleviates the distress, and if that doesn’t work she may try moving the baby away from the noise near the window and keep trying to make sense of the distress until she is able to alleviate it or soothe the baby. All of the time mother takes in the distress in a way that communicates to the baby that this is manageable.

Subsequently this concept has been developed in relation to organisations (Bion, 1961) and more recently to leaders (Stokes, 1994 Roberts, 1998) who play an important role in containing organisational anxiety and distress. Anyone who has taught a cohort, managed a team or led a department will know instinctively the extent to which this is an unspoken part of your role. Individuals and groups experience emotion in their work life, and this emotion can motivate and inspire, and also disable and distress. Both structures and relationships within organisations can provide containment and so make emotions more manageable for individuals and groups. Containment is not just a role pertinent to the leaders or managers of an institution but also to academics and support staff in their interactions with students.

By means of an example, let’s imagine a lecturer who has just had a tutorial with a student who she notices has suddenly become withdrawn, and who said during the tutorial that there was little point in submitting his essay as he couldn’t see the point of carrying on. The tutor knows that this student has a diagnosed mental health condition and is involved with the Community Mental Health Team but has seemed well this year. The Tutor is so anxious she can’t think what to do. The Tutor has a good relationship with her manager and knows can ask for help so she asks the administrator to sit with the student while she speaks to her manager. The manager listens calmly and empathically. As the tutor starts to calm down the manager gently reminds her of the procedures to follow and where she can locate them on the staff intranet. The tutor, having been able to recover her thinking returns to the student, expresses her understanding of how hopeless he feels, checks that he is not planning to kill himself and has company overnight and gains permission to contact the student’s community mental health team to inform them of this latest dip in mood and arrange a time for him to speak with them.

This example demonstrates how debriefing with her manager helped the tutor to gain containment for herself and to recover her capacity to think. The structures and procedures within the College supported and contained her further. This is a key aspect of the role of leaders, managers, academics and support staff in H.E – to take in the distress of students and staff, process it and help them to find a way to resolve or manage the situation.

Although there are many excellent leadership courses available to those leading in higher education there is little training or understanding around the psychological concept of containment and how to increase the containing function as a leader and the impact positively on the wellbeing of staff across an organisation which in turn has an effect on that of the student body. Neither is there sufficient acknowledgement of and recognition of the emotional and psychological work involved in providing ongoing containment for staff and students in a university and the need for support for those doing the work. As Bion (1963) later specified, the need for ‘container contained’.

The Nature of the Work

Menzies Lyth (1960) proposed the idea that the nature of the task that an organisation is set up to carry out impacts upon the emotions experienced by individuals in an organisation. Working in Higher Education often evokes both conscious and unconscious feelings around the desire to succeed and a fear of failure. Anxiety is also evoked in relation to the intimate and sometimes disturbing relationships between staff and students. Menzies claimed that individuals and organisations evolve particular coping mechanisms, which can take the form of unconscious social defences, as a response to the nature of the work to protect themselves from being overwhelmed by emotions. These coping mechanisms in Higher Education often manifest in one of two extremes, as perfectionism, over involvement with students and work, or, as absenteeism, detachment, withdrawal and denial of feeling, either of which can undermine the student-tutor or employee-leader/manager relationship. Being aware of the emotions evoked in particular settings and creating safe spaces for them to be processed can help reduce the reliance on unhealthy defence mechanisms. Once more, very few leadership or teaching courses include materials and equip staff to consider unconscious dynamics at play in the work, the defences employed to manage the emotions evoked by the work and the impact this has on the functioning of the staff and their delivery.

Behaviours, Attitudes and Beliefs

Behaviours are one of the most obvious and direct factors in creating the psychosocial work environment and staff experience of the organisation as a whole. Negative attitudes and behaviours have a negative impact on wellbeing and, if allowed to continue without consequence or worse, if seemingly rewarded, will be learnt as an accepted norm by other people, especially new joiners. Similarly, a culture where positivity is a must and distress, vulnerability or negativity is not allowed will be equally damaging. One of the behaviours we often see in higher education is the ‘always on culture’. Managers sending emails at midnight to staff and staff responding to students in the early hours of the morning perpetuates the ‘always on ‘culture that is detrimental to wellbeing. In addition, those who choose no longer to answer emails due to the overwhelming amount may evoke distress and anxiety in others.

Structures and Processes

Working or studying in well-structured environments with clear goals and timeframes alongside support from managers or tutors and having opportunities for contributing toward improvements at work and study are known factors that contribute positively to staff and student wellbeing. Having clear processes, procedures and lines of accountability that are easily accessible and transparent, assists both staff and students in navigating the university experience. Creating regular, consistent and time- boundaried spaces for staff to connect and reflect on and process the work that they do is a key structure that is often omitted from the fabric of the organisation due to increasing demands. This can lead to an inability to work things through, both individually, and as a team, department and organisation and can lead to unhelpful and repetitive patterns of behaviour, conflict, absenteeism, feelings of isolation or even burnout.

Psychological Safety

It is important for universities to create and maintain psychological safety, an environment where people feel able to be open and vulnerable and trust the organisation and people within it to be curious and to care about their psychological wellbeing. In a psychologically safe environment experiences can be more fully processed leading to greater learning and development.

This can be created by raising awareness around wellbeing, encouraging people to talk about how they feel in classes, meetings, social events. Through promoting peer support programmes, resourcing wellbeing and counselling services sufficiently, and developing structures that make space to check in with each other, the organisation demonstrates its commitment to providing a supportive and open environment. Departments and courses within universities contribute significantly to setting the scene for psychological safety. One of the key ways of doing so is through paying attention to how learning occurs and how successes, mistakes and failures are managed and responded to. The tone of feedback and attitude towards successes, errors and failures can help or hinder psychological safety and needs some consideration. This does not require institutions to compromise on excellence, quite the opposite, as reducing anxiety and providing environments where staff and students can really learn from mistakes leads to greater achievements and creativity.

Conclusion

This model is a not a definitive answer to staff and student wellbeing but it is a model that can be effectively applied to the H.E sector, for institutions to use in their quest to become or remain an organisation that considers wellbeing not as an add-on objective but as something that runs through the core of the institution. By reflecting on the five pillars in relation to their particular context and reviewing what might need adjusting, improving or celebrating year on year, organisations can provide a containing environment for its people which ultimately impacts positively upon their wellbeing, their effectiveness at work and their capacity to respond flexibly to external influences.

References

Bion, W.R. (1957). The differentiation of the psychotic from the non-psychotic personalities. In E. Bott Spillius (ed.) Melanie Klein Today: Developments in theory and practice. Volume 1: Mainly Theory. 1988. London: Routledge.

Bion, W.R. (1959). Attacks on Linking. In E. Bott Spillius (ed.) Melanie Klein Today: Developments in theory and practice. Volume 1: Mainly Theory. 1988. London: Routledge.

Bion, W.R. 1961. Experiences in Groups. London: Tavistock.

Bion, W.R. (1962). A Theory of Thinking. In E. Bott Spillius (ed.) Melanie Klein Today: Developments in theory and practice. Volume 1: Mainly Theory. 1988. London: Routledge.

Bion, Wilfred R. (1963). Elements of psycho-analysis. London: Heinemann

Menzies-Lyth, I. (1960) A case-study in the functioning of social systems as a defence against anxiety. Human Relations Vol.13 N0.2, p95-121

Roberts, V.Z. (1998). Is Authority a Dirty Word? Changing attitudes to Care and Control. In: A. Foster & V.Z. Roberts, eds. 1998. Managing Mental Health in the Community: Chaos and Containment. London Routledge, 49-60.

Stokes, J. (1994). The Unconscious at Work in Groups and Teams: Contributions from the World of Wilfred Bion. In: A. Obholzer & V. Roberts, eds. 1994. The Unconscious at Work: Individual and Organizational Stress in the Human Services. London: Routledge, 19-27.

Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust – The National Workforce Skills Development Unit. (2019) Workforce Stress and the Supportive Organisation – A Framework for Improvement through Reflection, Curiosity and Change.