Insight

Breaking the cycle of breaking New Year’s resolutions: why we so often fail and how to change

11 January 2024

- Why is it hard to change

- What is your goal?

- How do i get in the way?

- Hidden commitments

- Big Assumptions

- What next?

By David Sibley

The turning of a year can symbolise such hope for renewal and a moment to commit to the changes we want to make in our lives. But why is it that we so often break those resolutions?

Harvard academics Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey have thought deeply about what could be at the core of why this happens. So much so, they have created a practical tool to help us uncover what stops us succeeding in personal growth. The ‘Immunity to Change’ tool can help uncover hidden conflicts, psychological defences and unexamined assumptions that unconsciously influence our perception of the world and our ability to change. At Tavistock Consulting, we integrate this into a wider systems psychodynamic approach, which is a method of working with the emotional life of organisations and systems.

Below is the process of creating an ‘Immunity map,’ using Kegan and Lahey’s approach, which we want to encourage the reader to do – download a blank template here.

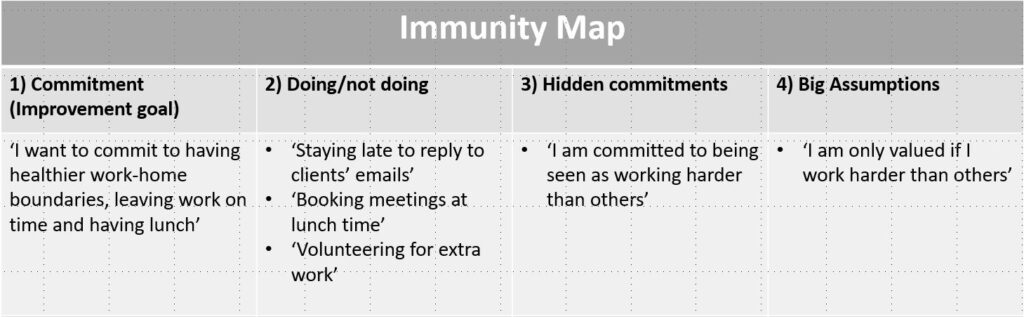

Column 1. What is your commitment goal?

What change do you want to make this year? Is there something you want to get better at but have struggled to make the change happen? Think of something that has frustrated you, a familiar pattern something you want to change and improve. For example, a commitment goal might be ‘I want to commit to having healthier work-home boundaries, leaving work on time and having lunch.’

Link your commitment to a value or need. So, in this case you want to model a healthy culture for your team and need to look after your health.

Useful questions to ask yourself:

- What goal do I want to commit to?

- Why do I want to make this change?

- What benefit could happen if this change happens?

Column 2. Doing/not doing

Next write a list about all the things that you did and did not do that conflicted with this goal. Be honest with yourself about behaviours that works against your ‘commitment goal’.

In this example, the behaviour might be staying late to reply to clients’ emails, booking meetings at lunch time and volunteering for extra work.

Useful questions to ask:

- How am I getting in the way of my commitment?

- What are the things I do that prevent me from achieving my goal?

- What are the behaviours I do and do not do?

This is often where people stop in their reflective thinking and then double down on making more effort to make the change. The ‘Immunity to Change’ approach goes a step deeper and uncovers the hidden functions of these behaviours.

Column 3. Hidden commitments

Breath into your body and connect with your feelings, now imagine if you did not do the behaviours in column 2, and you did the opposite. As you picture this, how are you feeling? What worries and fears emerge?

In the example, you may tune into worry that by not taking on extra work and timetabling in lunch, colleagues would think you are not working hard enough. Therefore, one hidden commitment could be ‘I am committed to being seen as working harder than others.’

Useful questions to ask yourself:

- If I imagine I did not do the behaviours in column 2, how do I feel?

- How have I been unconsciously protecting myself? What am I secretly committed to?

- How do I want to be seen by others? Or how don’t I want to be seen?

This column helps us discover our defences and the ways we protect ourselves. Lahey uses the metaphor of driving a car; we have our foot on the accelerator in column one and in column three we discover how we also have our foot on the brake.

Column 4. Big Assumptions

The next step is to determine the underlying assumptions that have been influencing your hidden commitments. If the opposite of column three’s hidden commitment happened, what bad thing do you think would happen?

In the example the hidden commitment was ‘to be seen working harder than others.’ The opposite is colleagues seeing the person not working hard enough and the fear would be losing their job or not being respected by colleagues. An underlying assumption is revealed – ‘I am only valued if I work harder than others.’

To access these underlying assumptions, ask yourself these questions:

- What emotion is driving my hidden commitment?

- What assumptions I am making that I think will happen if I do change?

- What assumptions I am making that I think other people will do or think if I do change?

These assumptions often link back to our past and will have a story. These beliefs unconsciously construct our reality. To put this another way the assumptions are like a lens in which you view the world through. Using the Immunity to Change approach however, you now get to examine that lens, rather than just looking through it. This has the potential to transform your mind and how you experience the world.

What next?

Finally, you now can examine assumptions that have previously been unconscious and effecting your ability to make change. You can think of this as starting a process to update your belief system.

In the example this would mean a personal shift from a behaviour of working too hard and measuring yourself against others for external validation to internally valuing yourself and your work. The level at which you choose to work can then transform to become a personal value that is internally measured and is not taken on defensively.

Useful questions to ask yourself:

- How realistic is this assumption, does it need updating?

- What is the story of this assumption?

- What support do I need?

Our meaning making internal systems can be updated by having new experiences, so do experiment and test out your old assumptions by having new experiences, and then let’s see how many New Year’s resolutions succeed!

This approach is also used in teams and with organisations. To find out more get a copy of ‘Immunity to Change’ or speak to us at Tavistock Consulting about how we can support your organisation.